About these clips of teaching in a Grade 1 class...

When WordWorks brought Melvyn Ramsden to Kingston in November 2006, many were not able to observe the most exciting part of his visit. For the two days we drove Melvyn around to four local schools so he could demonstrate lessons in classes from Grade 1 to 8. These video clips are good examples of word structure instruction.

Many assume morphological instruction is not appropriate until later years, so we wanted to share excerpts from Melvyn teaching in a Grade 1 class first. These students had no previous experience with instruction supported by Real Spelling or WordWorks, so this is an example of what can happen on the first instance of instruction that emphasizes the morphological structure of words. You’ll discover, however, that the lesson begins with very careful and explicit phonological instruction. These elements of orthography are interrelated, so appropriate instruction will reflect these elements of English spelling.

We apologize that the footage is not always beautifully edited. In order to respect the privacy of the children in these classes, you will notice that any footage had to be cut. When the picture freezes or goes black, that is the reason. The audio track continues so that you can hear the content of the lesson. Notes on the lesson:

All of the clips that follow were from the same session. Melvyn began with the word <helpful> that he noted on a class chart and asked if anyone would like to try spelling it. A child offered the misspelling <lufle>, which Melvyn dutifully transcribed as the child said each letter. From that starting point, Melvyn went behind the structure of the word <helpful> and worked with the class to build a large matrix on the base <help>. You’ll see that he later comes back to the child’s misspelling and shows that, although they were in the wrong order, each of the letters were used in the correct spelling of <helpful>.

There is a point I’d like to emphasize for you to keep in mind as you watch. While all of the language the Melvyn uses is linguistically accurate, there is nothing about this instruction that is difficult for teachers to learn, or too advanced for young children. There are a lot of concepts that teachers need to work hard to learn over time in order to teach children the details of the writing system, but we can start with the basic principles illustrated in these clips right away. Upon this foundation, and with the proper resources, teachers and students can start to explore and learn the details that come after this basic start.

-

1.Audio clip of using phonology to teach the base <help>:

Notice the emphasis on what pronunciations “feel” like. Melvyn’s instructions point children to what their lips are doing when they say /h/ or for the /p/ at the end of the word <help>.

-

2.Adding <-ing>: Building a word family

After using phonology (“tasting consonants”) to teach the spelling <help>, and discussing the meaning of this base, oral morphological instruction is used to introduce the written <-ing> suffix to the base <help>. Word building begins.

-

3.The matrix grows:

The morphological structure of words is consistently emphasized as Melvyn provides direct vocabulary instruction by extending the family of words built on the base <help>. Again all instruction centers around structure and meaning.

(Note: video freezes before audio finishes.)

-

6.Summing up -- expanding to other words...

In this clip Melvyn finishes teaching this part of the <help> family and plants the seed that the patterns they just worked with can be applied to countless other words that they already know. In fact, it does not need to take long before children see that the patterns they are learning from this type of word structure instruction are reliable tools for making sense of words that they don’t know.

-

5.From the matrix to word sums:

Melvyn sums up the matrix and introduces the word sum. This longer clip shows Melvyn introducing and consolidating important terminology that will help children discuss words and word structure for years to come. The word sum is a crucial tool for analyzing word structure. For those starting to teach with this tool, it is very helpful to watch the details of how Melvyn introduces it. I try to use these same principles whether teaching Grade 1 or Grade 8 students.

-

4.Reading and spelling from a word matrix:

Pay attention to how Melvyn gets students to focus on each morpheme, while they spell, and then read these words out loud. Also note how the conversation about the spelling and reading of these words revolves around structure and meaning.

Word Structure Instruction from the Start:

The beginning of a beautiful relationship – children and the written word

Peter Bowers

February, 2007

The instruction illustrated in the clips of Melvyn teaching the <help> word family represents what could be typical of children’s earliest introduction to the written word in schools. Literacy instruction targeting the structural frame of written words is designed to provide children with a foundational understanding that English spelling is a consistent and reliable system of meaning cues that can be investigated and understood.

With resources built on the consistent, interrelated structure (morphology, etymology and phonology) of English spelling, teachers can give children something firm to hold onto as they sort out how to take all that print on the page and process its underlying structures it into thought (reading), or as they learn to represent their thoughts with the structures of print (writing)1.

Working with the integrated structure that organizes how meaning is represented in print changes the way children perceive and engage with the written word. Typically, children are taught common letter-sound patterns to remember, but then are warned that because English spelling is “irregular” those patterns often fall apart for no apparent reason. Children are implicitly or explicitly told that we simply have to do the best with the irregular system we have been given. If this was how our system worked, I'm not sure what else we could do.

Typical spelling and reading instruction could be characterized as presenting and practicing common patterns in a complex and irregular system that is fundamentally about representing the sound of words in children's spoken vocabulary. Instead, we can introduce children to the system we have actually inherited – a complex, but well-ordered system that is fundamentally about representing meaning. When instruction is framed by the workings of our writing system, each new piece of information a child engages with is fixed to the existing structural understanding children are in the process of developing with expert guidance from teachers. As understanding of linguistic structure grows, children gain ever more power for integrating new orthographic concepts which are used to investigate new patterns and ever expanding families of words - always guided by the rudder that the spelling of words and word parts represent cues to meaning.

The teaching captured in the clips above show Melvyn introducing Grade 1 children to the basic underlying and organizing structure of written words. The lesson happens to use members of <help> word family. Countless word families could have been used to begin to set that structure in children’s understanding. The lack of suffixing changes or obvious pronunciation shifts in this word family are characteristics that make <help> a useful starting point. With the building block structure of words set in place, it won’t be long before a matrix on a word like <sign> could be used to add a new layer of linguistic understanding. The same building block nature of the written word applies to the family of words built on <sign> which include <signal>, <design>, <assignment> and <significant> among many others. With the <sign> family, however, children are shown that despite consistent spellings, pronunciation of morphemes can shift across words. With morphological structure in place, the interrelation of morphological and phonological representation in spelling can be more effectively integrated into an understanding of word structure that has already been developed through explicit instruction. Each new layer of word knowledge is easier to hold onto and make use of if it is built on an existing and accurate structural understanding. Building further, the word sum: sign + ate/ +ure signature could be used to introduce a next level of investigation – the consistent suffixing patterns. Each of these topics links back to and solidifies the foundation being introduced in Melvyn’s Grade 1 lesson.

Morphology and phonology: integrated structure – integrated instruction

It is important to clarify that the phonological structure of English spelling is a crucial element of this instruction at all levels of word study. The links between meaningful units of speech (phonemes) and the letter or letter combinations (graphemes) used to represent them need to be understood by teachers and explicitly taught. (See the audio clip beginning the lesson on the <help> matrix, or this article on the misspelling <*saycl>).

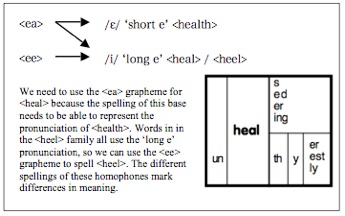

While the phonological element of spelling needs direct explicit instruction, this instruction should reflect its integration with morphology. As just one example of teaching a phonological lesson in the context of morphological structure, consider the lesson I recently taught to Grade 3 students.

A point I wish to emphasize is that when the phonology of spelling is taught in conjunction with morphological (and etymological) principles from the start, children need never develop the assumption that English spelling is irregular.

To summarize, typical instruction presents children with a complex irregular system. Instead, we can introduce children to the existing complex, but ordered system so that each new piece of information informs the next. In this way children develop a cohesive picture of how the spelling of words works. Children learn to count on their writing system, and the consistent patterns they have studied, as reliable tools for making sense and meaning of text.

Let me illustrate the distinction between these two forms of instruction by looking at how each might approach instruction of the basic word <does>.

Typical word study instruction:

As an “irregular” word, typical instruction might employ mnemonic devices and other rote memory strategies for this “sight word” (as a child I was taught to remember “dirty old eggs stink” for <does>). Aside from common frustration with this word, this experience reinforces the message that:

1) English spelling is often illogical;

2) Studying the spelling of words is largely a process of memorization.

Structural word study instruction:

The class that began its study of the English word with a lesson like the one illustrated in the video clips using the <help> matrix and word sums will have no difficulty making sense of these representations of the bases <do> and <go> and these members of their word families:

In this class, instead of trying to find an entertaining way for children to memorize the correct spelling of <does>, we can use this spelling to reinforce messages such as,

1.When working with spelling, always start with meaning;

2.Written words make structural sense;

3.Spelling of bases prefixes and suffixes remain consistent even when pronunciation shifts;

4.When studying a particular spelling we look for words of similar meaning and structures.

Obviously these messages are not ingrained in children’s understanding at the end of the study of this spelling, but in word study instruction based on word structure, students will return to these themes again and again, each time deepening children’s understanding.

The lesson built on these teaching tools, sparked by what may have initially appeared as a surprising spelling for the word <does>, can strengthen students’ understanding of many elements of English spelling. We can choose to use this spelling for phonological instruction by practicing "tasting consonants" to identify what our tongue and lips are doing for /d/ and the beginning of the word <does>. We can point out that the easiest way to write /d/ is the letter <d>. (Note that this wording acknowledges that there are other ways of representing /d/, but that this is a logical first choice). Another potential phonological lesson here is that the letter <s> is commonly used to represent /s/ or /z/. I like to teach this point by having children put their fingers on their throat as we say the words <cats> and <dogs>. We find that pronouncing the <-s> suffix in <cats> doesn’t make our throat vibrate, but in <dogs>, our vocal cords do vibrate. Regardless of how we pronounce it, if we want the suffix to mean more than one, we use the letter <s>.

Note how phonological lessons can be taught in the presence of the organizational force of morphological structure. Common misspellings of this word include <*duz> and <*dose>. These errors can be very productively analyzed to reinforce the structural spelling/meaning link. The first misspelling is incorrect because it would hide its connection to its base <do> (I do; s/he does). The second spelling is not possible because there is no suffix <-se>. By teaching a number of verbs and switching between the fist and third person, students can see the regularity of the <-es> suffix. Depending on the situation, this may be a good time to teach the patterns for when we use <-s> or <-es>. When common words are used as a vehicle from which to teach word structure, a wide variety of important potential topics about the written word present themselves. Whichever topic the teacher chooses, it will be one that now fits into the developing frame of understanding that the child is already building.

The matrix and word sums that we would practice writing as a part of this lesson instantiates the spellings, structures and meaning cues of these words. We don’t need to just teach the accurate spelling of the single word <does> and add it to the list of many tricky words on our word wall. If we’ve used these families of words to explain how these spellings work, we can post this matrix on the wall as a reminder of the concepts about spelling we learned from these word families. This explicitly taught morphological knowledge (including how this element interrelates with phonology) becomes added leverage for working with countless other words that children will be encountering.

The instruction I am describing here is firmly rooted in Dewey’s call for promoting generative educative experiences as he described in Education and Experience, “No experience is educative that does not tend both to knowledge of more facts and entertaining of more ideas and to a better, a more orderly, arrangement of them” (p. 82). Teachers require (and deserve) training and resources in the structure and purpose of English spelling if we expect them to help children build a generative understanding of the consistent, organized structure and purpose of their writing system.

Where dictionaries come in...

Inevitably, instruction of this type sparks highly motivated complex investigations of words and connections of meaning between words. This is one of the most striking characteristics I have seen over and over in classes working with a structural understanding of words. Teachers are often shocked (as I certainly was) when they first see a Grade 4 student race for dictionaries to test a theory of a spelling and meaning connection between words (Click here to see what happened when one of my students investigated <secret> and <secretary>). I’ve come to realize, however, that what is shocking is what little reason I was giving students to use dictionaries. They have access to spell checkers, and I was trying to get them to look in dictionaries to check spellings or learn word meanings one at a time. It would be hard to come up with a less motivating instructional design for dictionary use or word study.

If you review the examples of student work in the pages in this website you will see the consistent use of dictionaries (of various sorts) by both teachers and students. These classes are using these references because the way they are investigating words makes their usefulness apparent. There is a story I often tell from my first year of learning how to teach this way that was an early indication to me that something important and different was going on in my class. I was working with a Grade 4 student on a word sum. We reached a point where we needed to look at the root of a word to see if our hypothesized base made sense. The child went to the table where our growing pile of references was kept. When he saw that our big black “Dictionary of Word Origins” was not there, he was frustrated and turned around demanding of the class, “Who took the Ayto?!”. I had no idea that my students had come to refer to this 900 page reference text as “The Ayto” (the author’s name, John Ayto is prominently displayed on the cover). Another student had identified a question they wanted to resolve, and without consulting me, they knew that they could use “the Ayto” to help them in their own investigation. This was a classroom scene that just did not compute with my previous ten years of teaching. It wasn’t that I had created assignments to force kids to use dictionaries (as I had tried in the past), I was just teaching about the written word so that kids had questions they wanted to resolve, and they understood that dictionaries held answers they were seeking.

Vocabulary instruction

WordWorks has highlighted a recent book on the current research on vocabulary and reading comprehension (Wagner, Muse & Tannenbaum, 2007) on our Resources and Links page. In his chapter entitled, “Metalinguistic Awareness and the Vocabulary-Comprehension Connection” William Nagy (2007) discusses various aspects of how children think about text. One point he emphasizes is morphological awareness. He states, “One way that morphological awareness may contribute to comprehension is by facilitating the interpretation of novel morphologically complex words the student encounters while reading—in effect, on-the-spot vocabulary learning” (p. 64). Later in his chapter, he goes on to discuss the idea of increasing metalinguistic awareness as an instructional goal. He points out, “Getting children to talk about words is not just a means for them learning the meanings of specific words; it is a way to help them think in more powerful ways about their language” (p. 69).

Watch Melvyn Ramsden present fundamental structures of the writing system that show how words are built with Grade 1 students. Investigate the examples and descriptions of classroom instruction on this website. I would suggest that these are models of how we can build engaged, generative discussions about words with exact terminology and consistent patterns. A key step for encouraging children to investigate and discuss word structure is that we develop a clear lexicon about word structures that refine conceptual understanding and metalinguistic knowledge that students learn as they work with words. As is shown in the clips of Melvyn teaching that linguistically structured discussion can start on the first day of school.

----------------------

Endnote

1This framing of a learner’s interaction with the structures of print grows from my study of Ramsden’s argued justifications about assumptions about orthography upon which he bases his teaching with statements such as “[orthography] is human thought made visible as text” (Personal communication. For further investigation, see Ramsden’s eBook “Orthographic Analsysis” 2005 available as part of the Real Spelling Tool Box 2 from Ramsden at www.realspelling.com)

Copyright Susan and Peter Bowers 2008

Click this link for a pdf of this article.

do

go

es

ing

ne